Digital Defense in the Age of ICE

RC Concepcion – gyrelabs.org

Log onto Instagram and you’ll see reel after reel about rapid-response networks and organizations creating hotlines for “Know Your Rights” seminars, ICE-monitoring groups, and resources on how to document enforcement encounters. At the same time, you can switch over to media reports and see story after story of the administration’s use of ICE plowing through these very networks.

The fact of the matter is, if you’re holding a digital red card in front of an ICE agent, it’s already too late. Posting a sign on your home that says ICE isn’t welcome is more likely to be met with a kick through the front door than to serve as a deterrent. We treat these signs like garlic for Dracula.

Yet if you switch back to social media, you’re awash with video after video documenting individuals experiencing the worst day of their lives—their dreams ripped away, often illegally, by ICE and its administration

I don’t understand the disconnect. I believe these organizations are working with the best of intentions, and I deeply admire their dedication. But part of me wonders whether a misalignment between our vision for protection and our need to sensationalize social media creates a recipe

for tools that aren’t truly serving the communities most affected.

It’s time to recognize the reality of our current environment and evolve from a rapid-response mindset to a proactive community-defense model—something that combines documentation and witness tools with technology that truly addresses the needs of the people we aim to serve.

The Limits of Rapid Response

From what I’ve seen, rapid-response networks generally operate through a series of steps:

- Someone notices an incident.

- They contact a hotline to report it.

- A volunteer takes the intake.

- That intake is passed to on-the-ground resources.

- Alerts are sent to preset groups of individuals.

This system raises several questions:

- Are most users calling during an actual ICE encounter, or are they reporting general presence in their area?

- Is there a resource bottleneck when multiple people call the same hotline?

- How long does it take for an intake to activate a response group?

- How fast does this information reach the community?

Based on the (admittedly limited) research and anecdotal evidence I’ve gathered, many rapid-response cases are triggered when an ICE agent is already in direct contact with an individual. At that point, the rapid-response model has effectively failed that person. They had no advance notice, no chance to assert their rights, contact a lawyer, or gather documentation.

At that stage, the system shifts from prevention to documentation—tracking interactions, recording which agents were involved, and attempting to connect victims to human resources afterward. This process is important, but it doesn’t proactively protect the community at large. It creates records, not readiness.

The Verification Problem

Many organizations rely on teams of volunteers to source and verify information from social media and the web. Moderators must cross-reference posts to establish validity, but this process is extremely labor-intensive and introduces the risk of outdated or inaccurate data.

Assuming the first rule of the Internet—that nothing is true—how confident can we be that an image posted to Facebook depicting police activity is from the correct day, time, and place? Could it even have been AI-generated? Each unverified report becomes a bottleneck for already-overworked moderators, while every wasted minute brings another person closer to losing their ability to make an informed choice.

If the tools we’re giving communities are stale, unreliable, or easily manipulated, how can we measure their success?

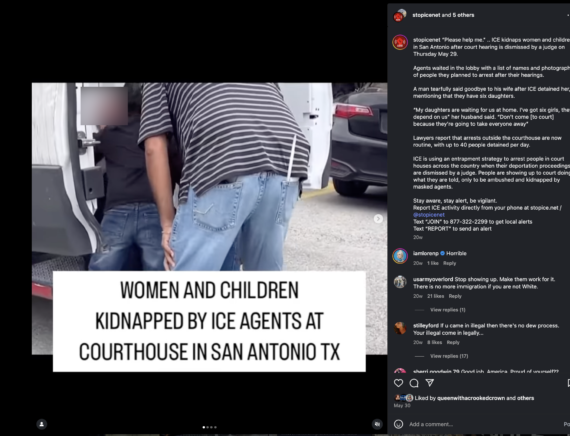

The Instagram Problem

While this critique applies to all social media platforms, let’s stick with Instagram. Scroll through immigration-related content and you’ll find endless talking-head videos repeating the same information. Every new post—“This just in…”—reports on another ICE capture, another outrage.

The result is an algorithmic rage loop.

Influencers and organizations compete for engagement, but the engagement becomes a collective scream of exasperation rather than a path toward change. The more followers an account gains, the more it feeds the loop.

Meanwhile, the people most affected—immigrants living in fear—are not on Instagram watching these reels. They’re working, surviving, and living under constant anxiety. These social-media cycles don’t reach them; they only amplify frustration for those already paying attention.

Social platforms have become tools that substitute real change with performance—activism theater. Influencers who could drive actual community impact are instead trapped chasing the next viral post. That might serve the algorithm, but it doesn’t serve the people we claim to protect.

Designing DEICER: A Proactive Defense

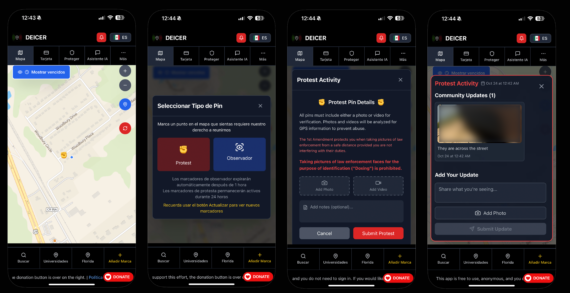

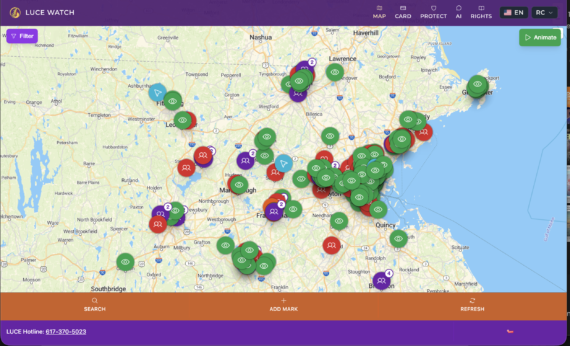

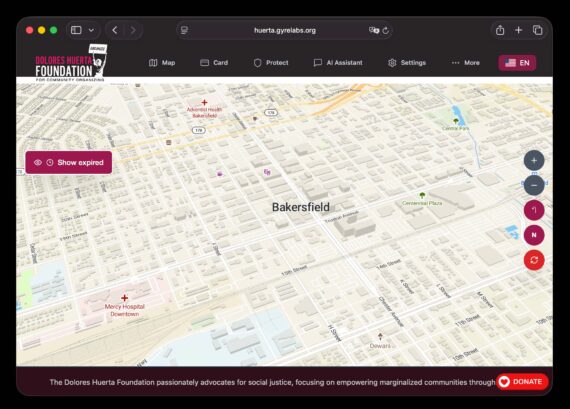

When I designed DEICER, my vision was to build a network of digital minutemen—a self-sustaining system of local defenders equipped with verified information. The concept was simple: download the app, teach others in your community to do the same, and create a living, breathing network.

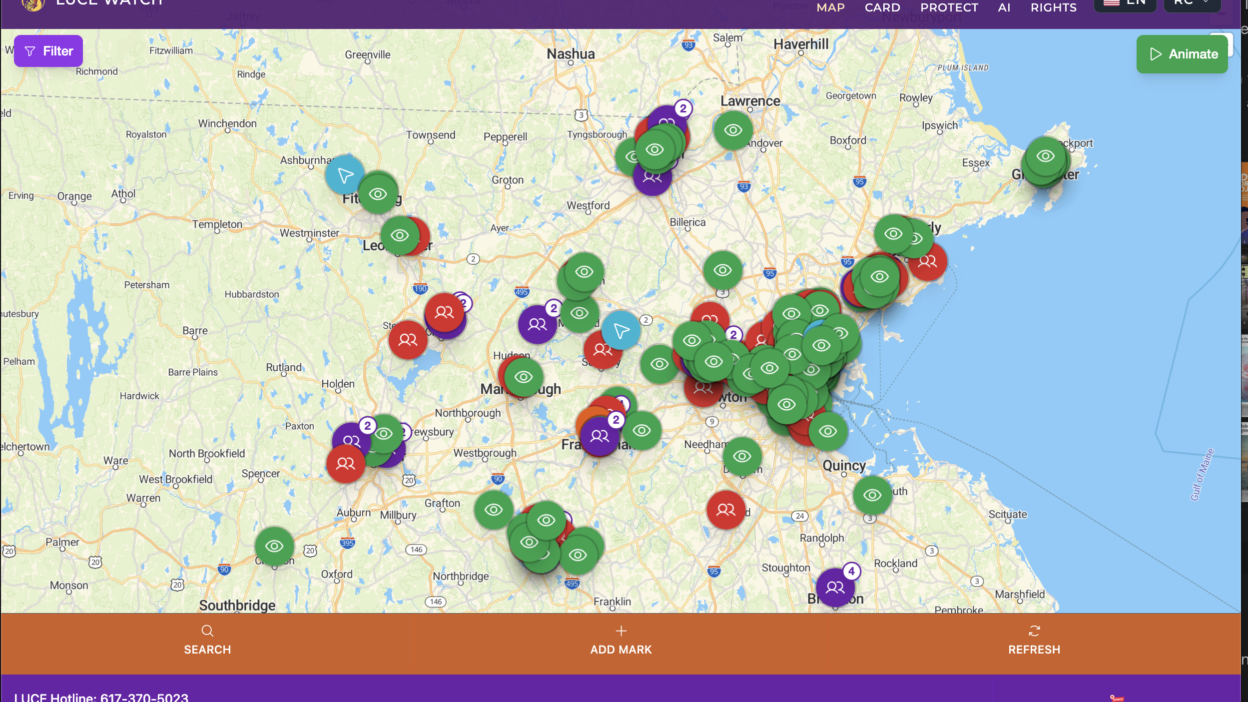

If someone spots ICE activity—a van at a gas station, agents gearing up, or cars stopped at a light—they can report it immediately through the app. DEICER only allows users to capture photos or videos within the app itself, automatically cross-referencing metadata (date, time, GPS) to prevent false uploads. If data doesn’t match, the marker is rejected

.

This validation ensures accuracy and eliminates the moderation bottleneck. Once verified, the alert appears on a shared map and automatically notifies users within the affected area. No one has to run down the street shouting warnings. The entire community knows instantly.

The purpose is not evasion—that’s illegal—but informed awareness. If we can receive lawful alerts about upcoming police checkpoints, upheld by judicial precedent, then communities should also have the right to know about ICE activity in their area. People can then make their own decisions: call a lawyer, gather documents, notify loved ones. It’s about agency—knowing what’s happening before it’s too late.

Augmenting Education Through Technology

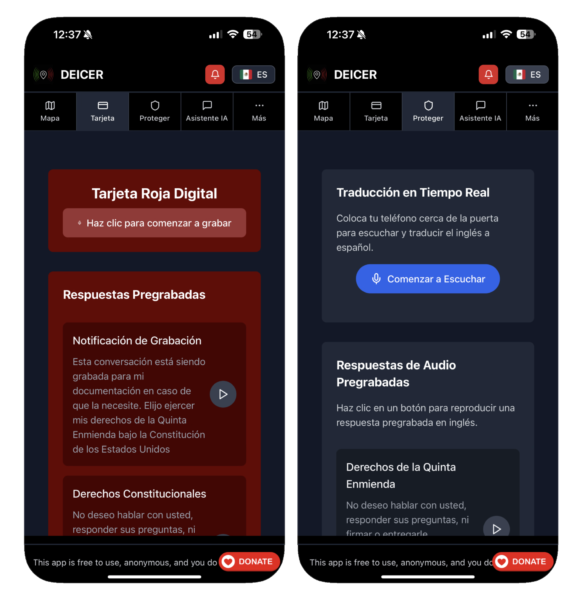

DEICER also includes tools to help users assert their rights. The app offers pre-recorded responses in clear, neutral English—so individuals don’t have to memorize legal language or risk escalation through misunderstanding. They can stay silent while their phone confidently speaks for them.

It also includes translation features. If an ICE agent knocks on a door and the resident doesn’t speak English—or speaks with an accent that might trigger profiling—the app can listen, translate, and respond appropriately in multiple languages.

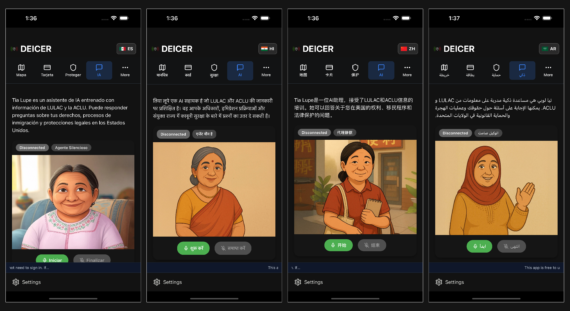

Two conversational AI agents power this system:

Tia Lupe” is trained on verified immigration and constitutional law sources. It answers legal questions in English, Spanish, Chinese, Hindi, and Arabic, and connects users to a human if needed.

“Pancho” provides interactive “Know Your Rights” training—adapting language, tone, and examples to each user’s needs. In one test, I asked it to explain rights through a *Harry Potter* analogy in Spanish. It instantly reframed legal protections as magical “spells,” using Hogwarts houses as metaphors for legal organizations. That might sound whimsical, but this type of hyper-customized learning can transform accessibility and retention across cultures.

I’m also developing new modules to help users study for civics and naturalization tests using the same adaptive model.

From Rapid Response to Community Defense

If we truly want to meet this moment, we must learn from voter-mobilization campaigns. Imagine if the energy spent maintaining rapid-response networks were redirected toward canvassing—teaching communities to use proactive defense tools like DEICER.

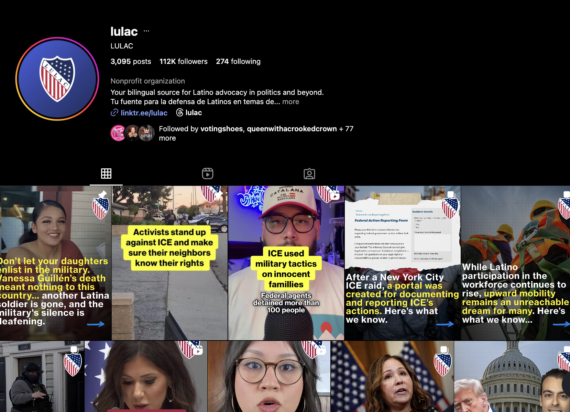

The infrastructure already exists: trusted local organizations. DEICER can create customized versions for each community. Siembra NC in North Carolina has its own version. LUCE in Massachusetts does too. In Chicago, I developed *Windbreaker* for any local organization ready to adopt it. Each is tailored to local needs but unified by one goal—community trust paired with technological precision.

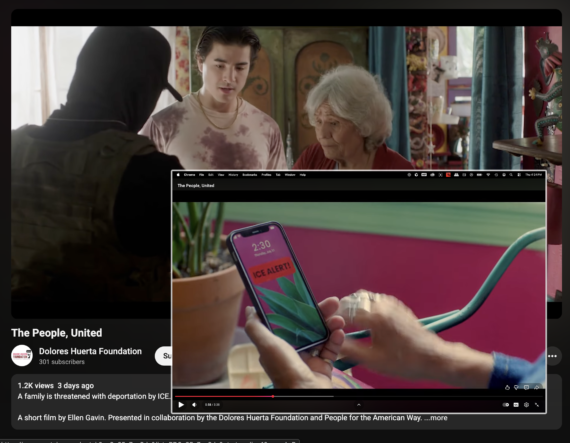

Recently, the Dolores Huerta Foundation released a short film dramatizing this idea: ICE agents trying to detain a grandmother, neighbors rushing to her aid, and an entire community chanting “¡Sí se puede!” outside her door.

It was inspiring—but the app shown in the film didn’t actually exist.

That’s when I realized: if people are ready to believe in this kind of coordinated defense, we should give them the real tools to build it.

I’ve since created a DEICER version that mirrors that imagined app—a concrete step toward making those stories possible.

Even Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recently spoke about the need for proactive community defense. Between grassroots groups and government advocates, there’s growing alignment around the idea that we need a smarter, faster, more verifiable system rooted in trust and technology.

This is the work I’m doing with DEICER. That’s the vision I’m committed to. I just hope more people will join in.